The following is an adapted excerpt from my upcoming book The Heart of a Cheetah: How We Have Been Lied to about African Poverty, and What That Means for Human Flourishing.

As a Senegalese woman married to a French man, living in the United States, twenty-something-year-old me was often overwhelmed by the disparity of wealth between my country and the other two. My husband Manu and I had been able to buy a home in Los Altos, one of the richest zip codes in the United States. Socially, we were very popular.

But I knew that so much of what people saw that they regarded as good in me they attributed to my Frenchness. I had European style, appreciated French cuisine, and had the manners of the French bourgeoisie. Most Americans did not really seem to respect Africanness. There is a heavy set of African American racial stereotypes, on the one hand, and then Black African stereotypes on the other (like “tribal,” “barbaric,” and “pathetic and starving”). Distinctive African cultures are almost entirely invisible to most Americans, Black and White alike.

The fact is that the Senegalese have tremendous style. Senegalese cuisine is delicious, and many Senegalese have tremendous nobility of bearing and refined manners. Senegalese people look regal, poor or not. But because the stereotypes of Africans are that we are barbarians, anything good about me must necessarily be French in the eyes of most Americans.

Of course, they were all kind, respectful liberals. But even then the default assumption was that Africans were tribal or, sadly, came from pathetic countries. The kindest people still tended to think of me as from a culture in which our children were all starving.

Yes, Africa is the poorest continent—and yet we also have a middle class, an upper class, art, culture, technology, manufacturing, etc. We are not where we want to be by a long shot, but we are not all flies-in-our-eyes UNICEF posters.

Still, it was useful to know that most Americans held these African stereotypes thanks to generations of tribal photos from National Geographic and countless fundraising images from UNICEF and other well-meaning charities. I needed to know what I was up against in order to fight it effectively.

But before I was ready to fight it, I first went through a phase of avoiding the issue. I convinced myself that this was not my cross to bear or injustice to fix. It was so big; it felt so unsolvable. And who was I to try to fix it? I, too, had a life to live. I deserved to live my life—to build a life.

And yet...why can people who are born in North America or Europe just go about enjoying their lives? Their only job in this world is to build a good life for themselves and their families. Why was it that I, on the other hand, could not just do that? It was not fair. It was damning and daunting.

Then something happened.

On a beautiful Saturday, I decided to take a car ride down the Northern California coast on Highway One. It was a glorious afternoon. I was alone in my car, driving along the winding road that is perched up high, with the majestic Pacific Ocean below spreading as far and wide as the eyes can see. The warm sun was hitting my face. I had Youssou N’Dour, a Senegalese Grammy award winner, blasting in my car.

All was going well. I felt a tremendous sense of accomplishment. Manu and I had made it through the early days and years of his business. We had worked really hard, and it had paid off. After a year or so, I had moved on with my own career, working mainly as a headhunter in finance.

I took a job with a multinational recruiting firm specializing in finance (then called Accountants On Call, or AOC, and now called Ajilon Finance, which is part of Adecco, a huge multibillion-dollar company). I picked it because my territory was going to be Silicon Valley. I loved the idea that I would be working with startups. Soon I came to work with customers like Google and Netflix before they became household names. At the time, these companies were in tiny little nowhere offices. No one knew what they would become. I was doing very well for myself. Very well. I was Rookie of the Year my first year—in the whole company, out of thousands of people!

And it only got better and better from there.

This little girl from a tiny village in remote Africa was now a success in Silicon Valley, the spring from which the biggest economic revolution in modern history arose! Unlike the Industrial Revolution, which sprang from the increasing use of machinery, the Digital Revolution was fueled by ideas. Billionaires were sprouting up like wildflowers. And there in the valley, I was, as they say now, killing it!

I could not help but feel the warmth of vindication in my heart as I was driving down that beautiful coast. But then, all of a sudden, it hit. As it so often did when I began to feel pride and joy in myself and my work, my thoughts turned to Senegal and the people in Senegal. My mood then turned sad, dark, and defeated, just as it always did.

But this time there was something different about the intensity of the pain I was feeling. Whatever it was, it was such a violent hit that I jerked a bit in my driving and almost left the road. If I had not gotten a hold of myself in time, I surely would have ended up in the ocean down below.

I was shaking, and I stopped at the first opportunity I found on a side road. There I wept and wept and wept. I was simply no longer able to reconcile the life of abundance I was afforded in the United States with the life of scarcity that existed back home in Senegal and in most of Africa. Yes, I had worked very hard to get to where I was, but still. The people back home were working very hard too. I was insanely overwhelmed and started feeling like I was suffocating.

I got out of the car and advanced toward the ridge. I faced the ocean. At that moment something happened. I have no explanation for it. But the fact remains. I just stood there, looking at the immensity of the ocean. I started to feel the wholeness and vastness of the ocean enter me through every single pore of my skin.

As it filled me up, I started feeling super light, but super grounded at the same time. It is at that precise moment that I made a pact with God. I said, “God, I surrender. From now on, I vow to devote every single breath of mine to the betterness of my Motherland. I do not know what to do or where to start. Please show me the way. Please put me to use.”

I got back in my car, turned around, and drove back home. Everything felt different. And everything would be very different from then on.

Unless you are from a poor country, I think few people can understand how it feels to watch your people suffer from poverty and the disrespect and patronizing “care” that comes along with it.

—Magatte Wade, from The Heart of a Cheetah

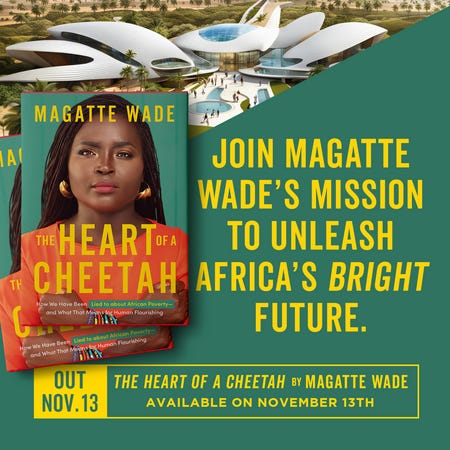

We’re only 2.5 weeks away from the release of The Heart of a Cheetah, and I am so excited to share my plan for African prosperity with you!

Pre-orders are available here. And you can sign up for updates about the release and special promotions here.

Thank you all for your continued support for Africa’s Bright Future!

"There is a heavy set of African American racial stereotypes, on the one hand, and then Black African stereotypes on the other (like “tribal,” “barbaric,” and “pathetic and starving”). Distinctive African cultures are almost entirely invisible to most Americans, Black and White alike"

You echoed my thinking and to add onto that, much information about Africa is missing. Some think it is a country and not a continent. Politics, culture, language, diversity, social life, and much more are yet to be fully explored. Almost every parameter used to gauge Africa is flawed. From credit rating facilities to its potential, every dimension is under explained. I am from Kenya. I write the Startup from Africa newsletter. I am happy for you spotlighting the continent.

Well done